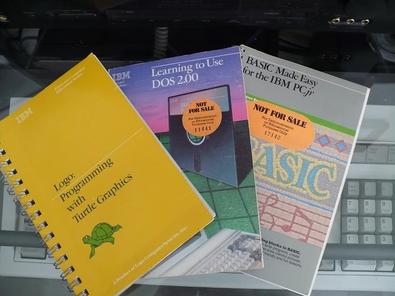

Around 1986, I discovered Logo. It came on a cartridge for my PCjr, and I was very excited to find out there was more than one programming language in the world. (I know, how did I not know this? We lived in a pre-Internet world, though, and I lived in super-rural Alabama, so you found out a very selective group of facts at a time. One of my memories I love so much is when I’d go to the Sam Goody in the mall in Columbus, GA after my orthodonist appointments and buy cassettes from the bargain bin at the front of the store based solely on their cover. I managed to find out about both Fugazi and the Cramps this way. Anyway, Logo.)

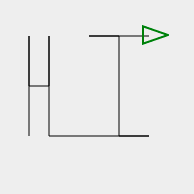

Logo was a very different language. It all revolved around the idea of a “turtle,” a little arrow on your screen you controlled via programming. Here’s a very simple sample:

forward 100 left 180 forward 50

left 90 forward 20

left 90 forward 50 left 180 forward 100

left 90 forward 100

left 180 forward 30

right 90 forward 100

left 90 forward 30 left 180 forward 60And you’d end up with this:

Logo was invented by several people including Seymour Papert. Papert is a mathematician that collaborated with Jean Piaget and has spent much of his life thinking about how computers could help children learn. He wrote an amazing book called Mindstorms with his thoughts on educational computing that I found a few years ago and read. He became one of my role models after reading that. How could you not love a guy who says things like:

The central question for educators is whether schools of the future will go on teaching the same curriculum, using computers to do the job better, or whether we’ll see radical change in what is taught and what is learned in schools. In my address I shall suggest that the education system will not be able to bring itself to decide on radical change in the curriculum. But there will be radical change all the same, despite the system’s lack of decision-making power.

and

The role of the teacher is to create the conditions for invention rather than provide ready-made knowledge.

I love these words on Logo from him:

Logo is much like a natural language such as English. Baby talk allows the child an easy way to grab onto and use pieces of the language. But nowhere in the world is a language restricted to baby talk. The child continues to be immersed in the full richness of language as used by philosophers and poets. It is the quality–the rich complexity that opens up as one explores Logo ever more deeply–that makes Logo “good for children” and for adults as well.

Logo was not a commercial success, as you might imagine. Many people might say it was not even successful at its goal of helping with educational computing, although I’d disagree. I think ideas from it still echo through educational computing today. The Bootstrap curriculum, which I taught in a local middle school’s after-school program definitely has Logo influences all over it.

Logo also resembles Lisp, another ancient language that has been in the shadows for a long time. One of the more modern iterations on Lisp is Clojure, a language I’ve grown to love and enjoy programming in more than just about any other.

Last year, I found a board game called Robot Turtles made to teach basic programming concepts to children 4 and up. Although my son was 2 at the time, I bought a copy to save for him. When I opened it up, as I guessed, it was a simplified version of Logo, where kids program with cards and the adult has to act like the computer. My kid loves telling me what to do, so I think that’s going to work out well.

If you don’t think you know how to program and you’re reading this, I recommend going to Turtle Academy and spending some time playing with Logo. You’ll likely have a lot of fun.

For anyone, I recommend going to The Daily Papert and signing up to get a quote from Dr. Papert every day in your email. I definitely get big smiles every time I read one of his quotes.